Exotic Containerization in the Wild

Looking beyond the conventional configurations to see what containerization can do when the kernel, runtime and host are pushed to their limits.

In this post we will cover some deeply technical topics but not in-depth, so we can still see the forest for the trees. Namely, ways in which containers are used to provide services and capabilities at scale for features that hum silently in the background from serverless functions (AWS Lambda, Google/Firebase Cloud Functions, OpenFaaS) and local Kubernetes cluster upgrade testing that can serve millions through per request containers to CI/CD systems(Azure DevOps, Github Actions, BitBucket Pipelines) and self-cannibalizing container image building environments (BuildKit, kaniko, makisu, buildah).

While we will not cover the conceptual basics of Docker, to better set the stage, let’s refresh how Docker and other container engines work behind the scenes.

Core Architecture and Technical Foundations

The Container Model

At its foundation, Docker leverages Linux kernel features to create isolated execution environments. Windows (for Linux containers HyperV/WSL2) and MacOS (Alpine Linux VM on Apple’s Hypervisor/Virtualization.framework) fundamentally run Docker through a Linux virtual machine where the containers are actually created and run.

The primary mechanisms include:

Namespaces provide process isolation by creating separate views of system resources. Docker uses multiple namespace types: PID namespaces isolate process trees, network namespaces provide independent network stacks, mount namespaces create isolated filesystem views, UTS namespaces separate hostname and domain names, IPC namespaces isolate inter-process communication, and user namespaces map container users to different host users for security.

Control Groups (cgroups) manage and limit resource consumption. They restrict CPU usage, memory allocation, disk I/O bandwidth, and network bandwidth for each container. This prevents individual containers from monopolizing host resources and enables predictable performance characteristics.

Union Filesystems enable Docker’s layered image architecture. Technologies like OverlayFS, AUFS, or Btrfs stack multiple filesystem layers, allowing efficient storage and rapid container instantiation. Each layer is read-only except the topmost container layer, which captures runtime changes.

As Docker did not appear out of the void, it builds on the shoulder of giants, the foundational components are provided by the Linux kernel and it’s modular scalable design with the above mentioned namespaces, cgroups and union filesystems. From the most run-of-the-mill to the more exotic implementations, they all tweak the dials and knobs provided by the foundational components above.

Exotic Usages

1. Triple-Nested Docker (Docker-in-Docker-in-Docker) for CI/CD

As this is covering the more advanced patterns we consider

DooD (Docker-outside-of-Docker)

Container mounts the host’s Docker socket

/var/run/docker.sockinto a container without running a separate daemon. The container uses the host’s Docker daemon to create sibling containers rather than nested ones.

Docker-in-Docker (DinD)

Container mounts the host’s Docker socket into a container running its own Docker daemon. This creates a fully functional Docker environment within the container. However, this technique has significant security implications. The inner Docker daemon requires privileged mode, granting extensive access to host resources. Volume mounts can access the host filesystem. Nested containers may bypass security policies.

as known and will not go in depth on them.

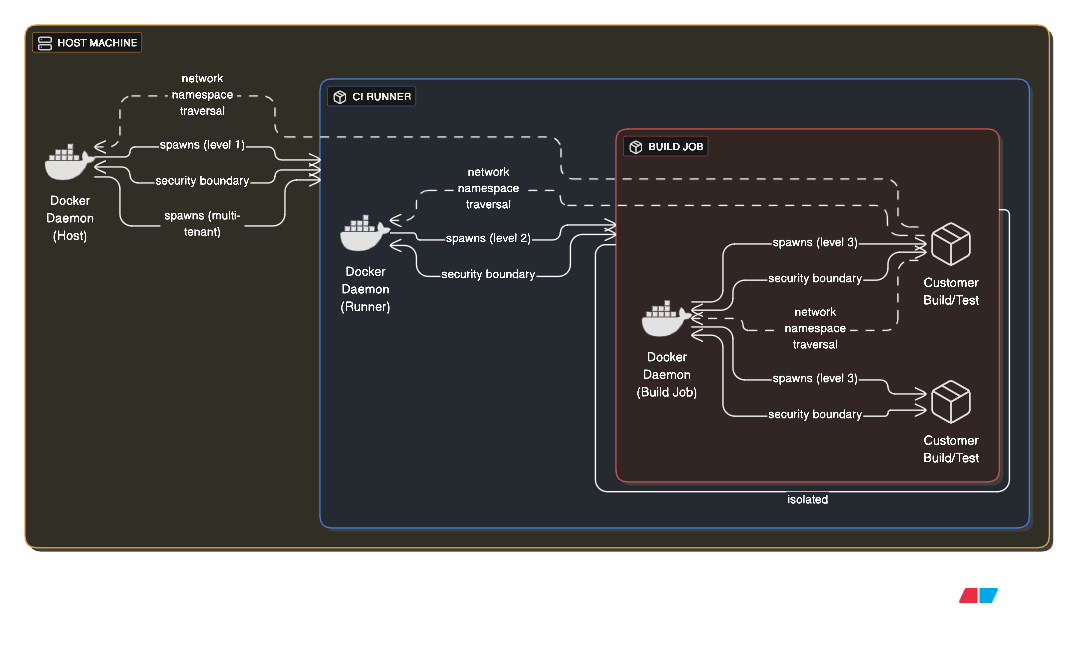

Instead, by building on top of DinD we can have DinDinD (Docker-in-Docker-in-Docker) which, while it may seem an anti-pattern, is used in CI/CD platform to provide isolation of client pipelines as follows:

A host runs Docker, which spawns a CI runner container (first level), which spawns build job containers (second level), which themselves build and test Docker images (third level).

This extreme nesting creates massive complexity. Each layer adds overhead and potential failure points. Security boundaries become unclear as privileges cascade through layers. However, multi-tenant CI platforms sometimes use this to provide complete isolation between customer builds while allowing those customers to use Docker themselves.

The above paradigm can be seen in action, for example, on AWS ECS Fargate serverless containers which do not allow privileged mode to avoid “noisy neighbours” meddling with other containers running on the respective host. This famously prevent ECS Fargate from being used as build agents for various CI systems that allowed “on-premise/custom agents” such as GitLab/Github/TeamCity.

2. Kubernetes-in-Docker (KIND) Clusters

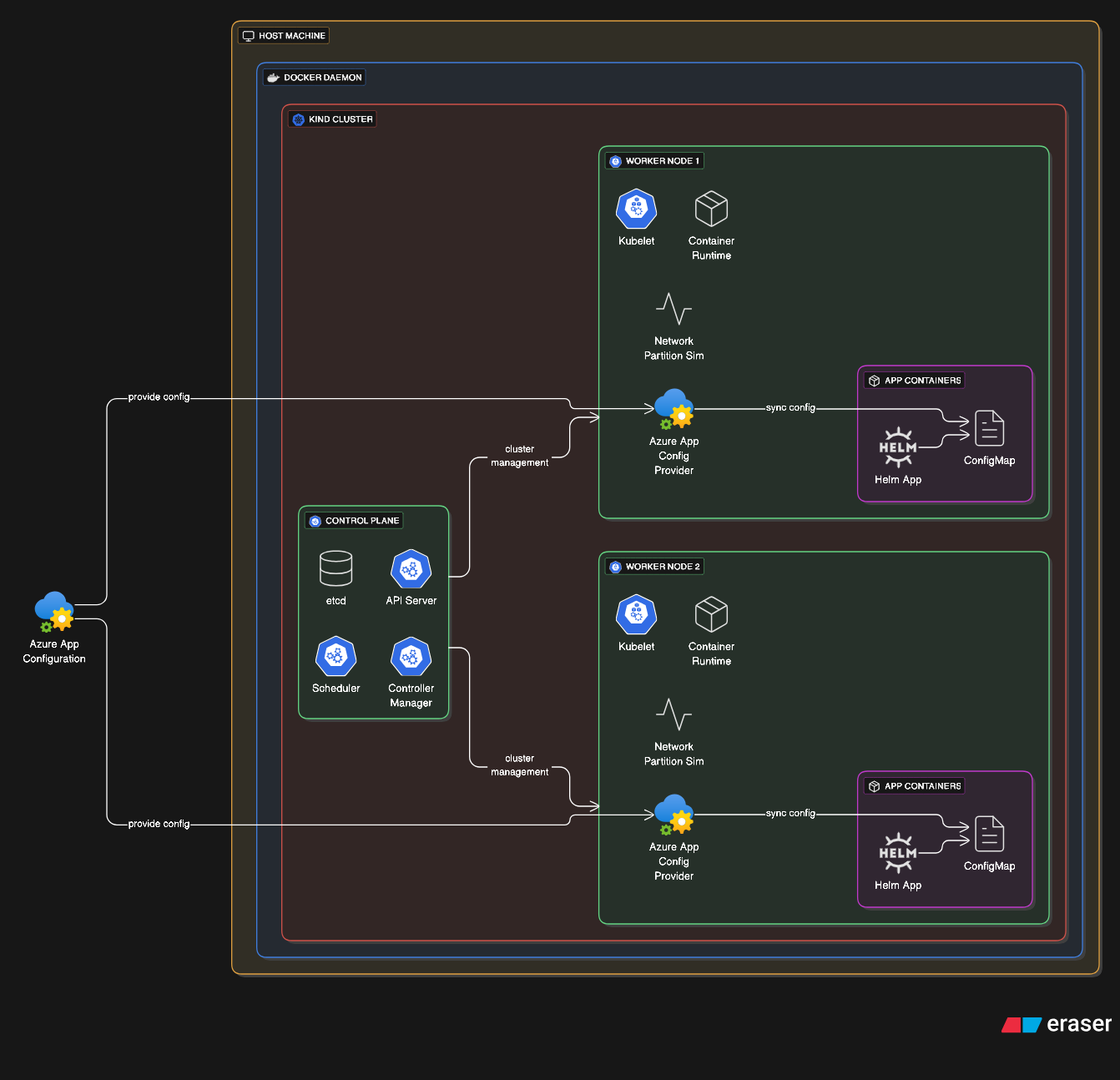

Kubernetes-in-Docker runs entire Kubernetes clusters inside Docker containers. Each Kubernetes node becomes a Docker container, creating a full cluster on a single machine. This pattern serves local development, CI/CD testing of Kubernetes manifests, and training environments.

KIND creates a control plane container running etcd, API server, scheduler, and controller manager, plus worker node containers running kubelets and container runtimes. The outer Docker manages these node containers while the inner Kubernetes manages application containers inside those nodes. This recursive structure enables testing cluster upgrades, multi-node networking scenarios, and cluster federation patterns without requiring actual infrastructure.

The exotic aspect is running production-scale distributed systems architectures in a development laptop environment. Teams can test complex failure scenarios like node crashes, network partitions, and rolling updates entirely locally.

To a less extreme, one can leverage KIND to test out helm deployments of complex applications and provide integration testing for charts that have multiple properties that can be tweaked to ensure all scenarios are valid and functional. Of course, provider specific integrations such as AzureAppConfigurationProvider that links Azure App Config to a Kubernetes native ConfigMap requires more setup on the local cluster level.

3. Ephemeral Per-Request Containers

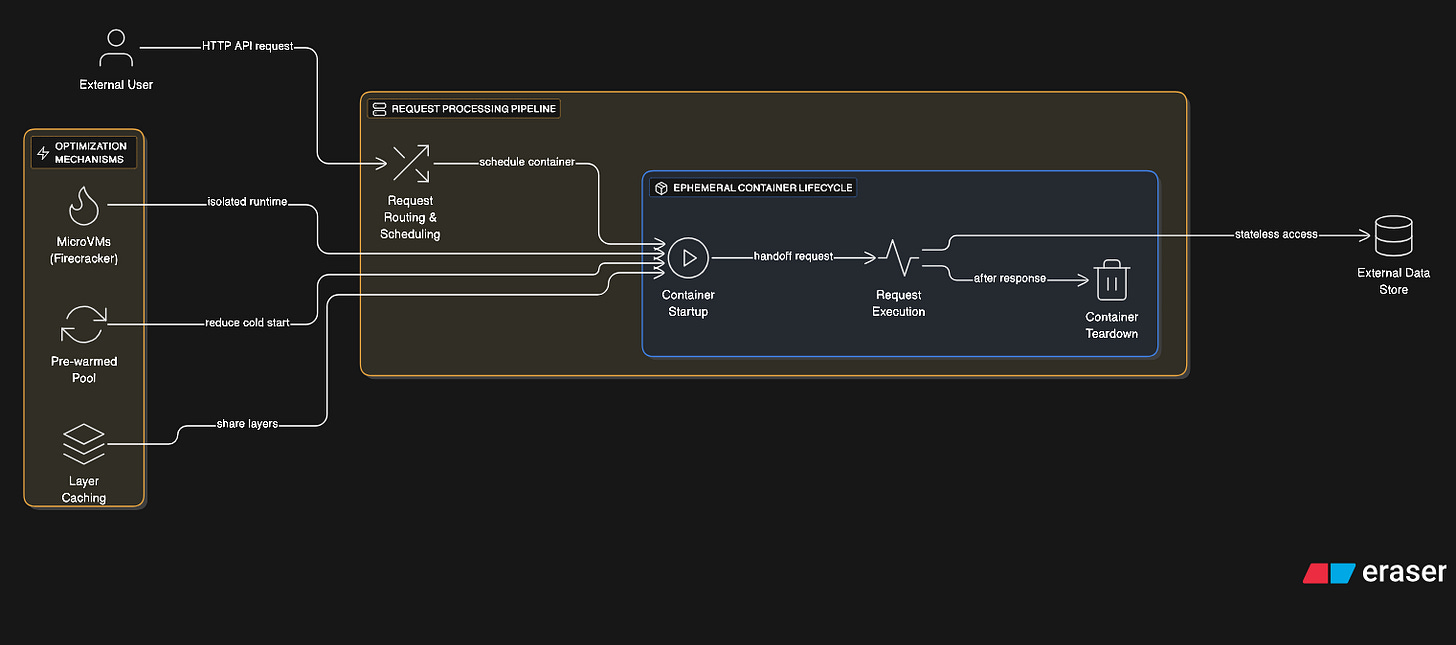

Some architectures spawn a fresh container for every HTTP request or function invocation (AWS Lambda, Google/Firebase Cloud Functions, Azure Functions, OpenFaaS). Each request gets complete isolation with the container destroyed after response completion. This provides ultimate security isolation at the cost of startup latency.

Optimizations for this pattern include pre-warmed container pools, aggressive layer caching, and checkpoint/restore functionality. Technologies like Firecracker combine container and microVM concepts for sub-second isolated environment startup. Container snapshots enable instant restoration to specific states without full initialization.

Through extreme optimizations and bespoke runtime creation, we can obtain container runtime’s feasible at scale that serve a wide variety of use cases from updating your cart to gathering data on the latest geomagnetic storm from IoT sensors.

4. Container Network Chaining

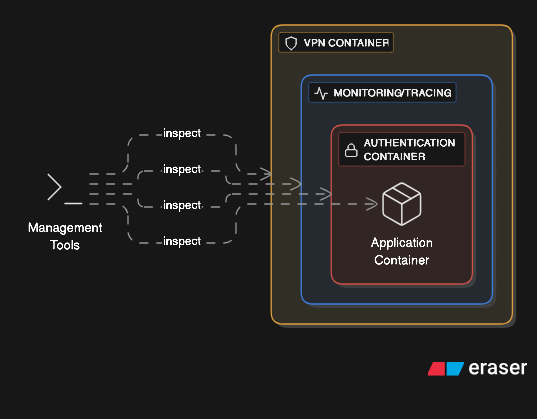

Advanced networking creates chains where container A’s network namespace contains container B, which contains container C, creating nested network isolation layers. Each layer can implement different network policies, firewalls, and routing rules.

This pattern enables sophisticated security architectures. An application container sits inside a network policy enforcement container, which sits inside a monitoring container, which sits inside a VPN container. Each layer adds specific network behavior without modifying the application itself.

The complexity becomes managing IP routing, DNS resolution, and network debugging across multiple namespace layers. Tools must traverse the entire chain to inspect traffic. Performance degradation from repeated packet processing across layers requires careful measurement.

This onion layered architecture permits the addition of advanced features on the edge of the application for security, monitoring, authentication and caching among other.

5. Distributed Filesystem Inside Containers

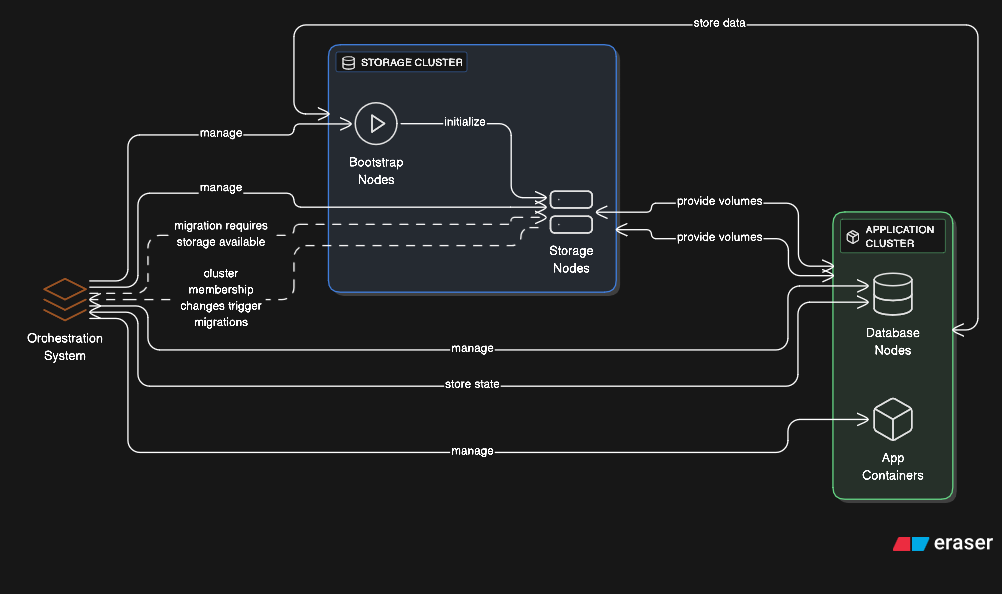

Distributed storage systems like Ceph, GlusterFS, or Minio run entirely in containers, with each container providing storage nodes. The containers themselves use Docker volumes backed by the distributed filesystem they’re implementing, creating circular dependencies.

This chicken-and-egg situation requires careful orchestration. Bootstrap containers initialize the distributed storage, then regular application containers consume it, including the storage system’s own persistent data. Storage cluster membership changes trigger container migrations, which depend on the storage being available during migration.

Some architectures take this further by running database clusters where each database node is containerized, storing its data on a distributed filesystem provided by other containerized storage nodes, with the entire system using container orchestration that itself uses the database for state management.

6. Container-per-File Isolation

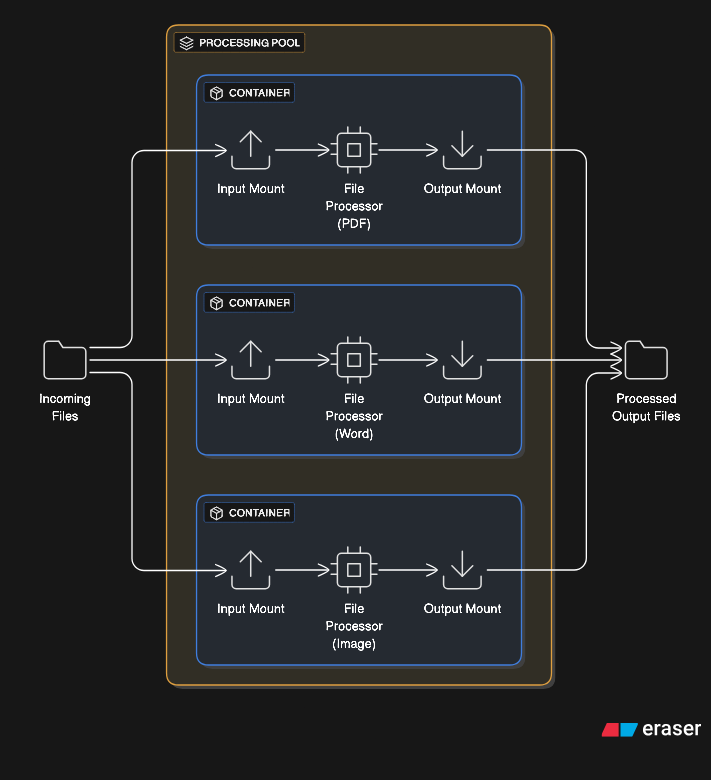

Extreme security architectures spawn a container for processing each individual file. Document conversion services might create a container for each PDF rendering, Word document processing, or image transcoding task. The container reads one input file, processes it, writes one output file, and terminates.

This pattern prevents malicious documents from compromising the system. Even if a specially crafted file exploits the processing software, the compromise is contained within a disposable container with no access to other files or system resources. The overhead is enormous but provides ultimate isolation for processing untrusted content.

Implementations optimize with container pools, volume mounting strategies, and parallel processing. A service might maintain 100 idle containers ready to process files instantly, with containers recycled after handling a configured number of files to prevent resource leaks.

This paradigm is useful when dealing with sensitive PII information, such as Stripe when dealing with uploaded documents leverages a similar architecture to ensure your passport or financial documents are processed in a secure enclave.

Conclusion

These exotic container patterns reveal a fundamental truth about modern infrastructure: the line between clever engineering and controlled chaos is being blurred ever so slightly more with each new implementation. What began as a simple abstraction layer—isolating processes from one another—has evolved into recursive, self-referential architectures that push the boundaries of what’s architecturally sensible.

The patterns we’ve explored aren’t merely technical curiosities. They represent real-world solutions to genuine problems: multi-tenant isolation, zero-trust security, ephemeral compute at planetary scale, and the democratization of complex distributed systems. A developer testing Kubernetes deployments on their laptop using KIND would have needed a datacenter rack a decade ago. A serverless function serving millions of requests through per-invocation containers achieves security isolation that was once thought impossible at scale.

Yet each pattern carries a warning. Triple-nested Docker environments create debugging nightmares. Per-request containers burn CPU cycles on initialization overhead. Sidecar proliferation can make the cure costlier than the disease. The distributed filesystem bootstrapping dance could be prone to race condition making the AWS DynamoDB DNS updating race condition that took down a good chunk of the internet child’s play. These aren’t anti-patterns to avoid—they’re calculated trade-offs where security, isolation, and flexibility are purchased with complexity, resources, and operational burden.

The future promises even more exotic arrangements. WebAssembly runtimes in containers, confidential computing enclaves nested within isolation layers, and quantum-container hybrids (should they ever exist) will continue blurring the boundaries. The containers we consider extreme today will become tomorrow’s baseline.

The true mastery lies not in implementing these patterns because you can, but in knowing when you must. Understanding these exotic architectures equips you to make informed decisions when standard approaches fail, when security requirements escalate, or when scale demands innovation.

Docker didn’t emerge from the void—it built on giants. These exotic patterns aren’t departures from that foundation; they’re proof that when you provide powerful primitives, engineers will compose them in ways you never imagined. The namespaces, cgroups, and union filesystems that enable a simple web server also enable recursive complexity that would seem absurd if it weren’t solving real problems at scale.